Returning to my preoccupation with my value as an artist, I’m chewing over the question of whether there is any uncontested ground on climate change mitigation and adaptation, biodiversity conservation or the need for adaptive cultural change. I consider myself broad-minded but there are times when I despair at the self-righteous, human-centricity of the arguments over what’s needed to ensure a viable future for the planet.

British philosopher and Nobel Prize (Literature) winner of 1950, Betrand Russell’s words have been floating across my screen on various platforms over the past couple of weeks. Some algorithm has suggested that my musings of late are in line with what he has to say. The opinions that are held with passion are always those for which no good ground exists; indeed the passion is the measure of the holders lack of rational conviction. Opinions in politics and religion are almost always held passionately. – from ‘Sceptical Essays’, 1928.

I wonder if Russell would have included human-induced climate change in that mix? I have friends and acquaintances who have spent years studying various forms of science at university, some with doctorates, going on to spend more years working in the field, yet frequently ending up in debate with people who haven’t invested this time in their education, observations and peer scrutiny. Why does this happen? There’s the issue of poor science extension communications, but there’s also uncertainty — a constant in life and scientific method, but something that doesn’t suit governments and institutions, or the general public. So, while leaning into uncertainty can provide an opportunity to communicate issues and build trust, instead we’ve seen growing distrust. This has left us all the poorer in an unstable world that despite all the technology available, still has extremely low levels of digital literacy that continues to mislead many.

Stories of a better world

Some believe that with all the political instability in the world — riding on the wave of climatic instability, we’ve lost our trust in any form of authority, not just scientists but governments, public service, and media. In her book, How to Talk About Climate Change in a Way that Makes a Difference, Rebecca Huntley talks about an interview she did with Tony Leiserowitz, Director of the Yale School of Environment’s Program on Climate Change Communication. Huntley writes of the conversation: One of the biggest tasks of the climate movement, Leiserowitz told me, is to create a positive, alternative view of the future… “We don’t tell an alternative story of a better world we want to live in. That leaves a cultural vacuum for our opponents to fill and they’re happy to do it.”

Who better than artists to help tell that story? This is something we do well. If, as Leiserowitz suggests to Huntley, natural scientists are important and great at helping us understand the challenges and why they happen, but maybe not so great at understanding human perception, decision-making and behaviour, why aren’t we seeing more collaborative, co-led endeavours between the social sciences and humanities/ arts to breach the gap? I know it’s happening in some universities, but rarely outside the halls of academia and rarely co-led. As someone who has an interdisciplinary practice, a background in systems agriculture and natural resource management communications, and who is keen to work on projects of this nature, it’s incredibly frustrating to find so few doors open. Regardless, I’ve tried to make my own way.

A line from an essay about the Scottish Gàidhlig poet, Somhairle MacGill-Eain has been stuck to my computer for the past few weeks. It basically talks about taking what the outer eyes sees and understands that represents, to one that is understood by the inner eye. I feel it aligns with my desire to explore the layers of nuance and complexity within the rural and regional territories, seeking the hidden elements that make them vibrate.

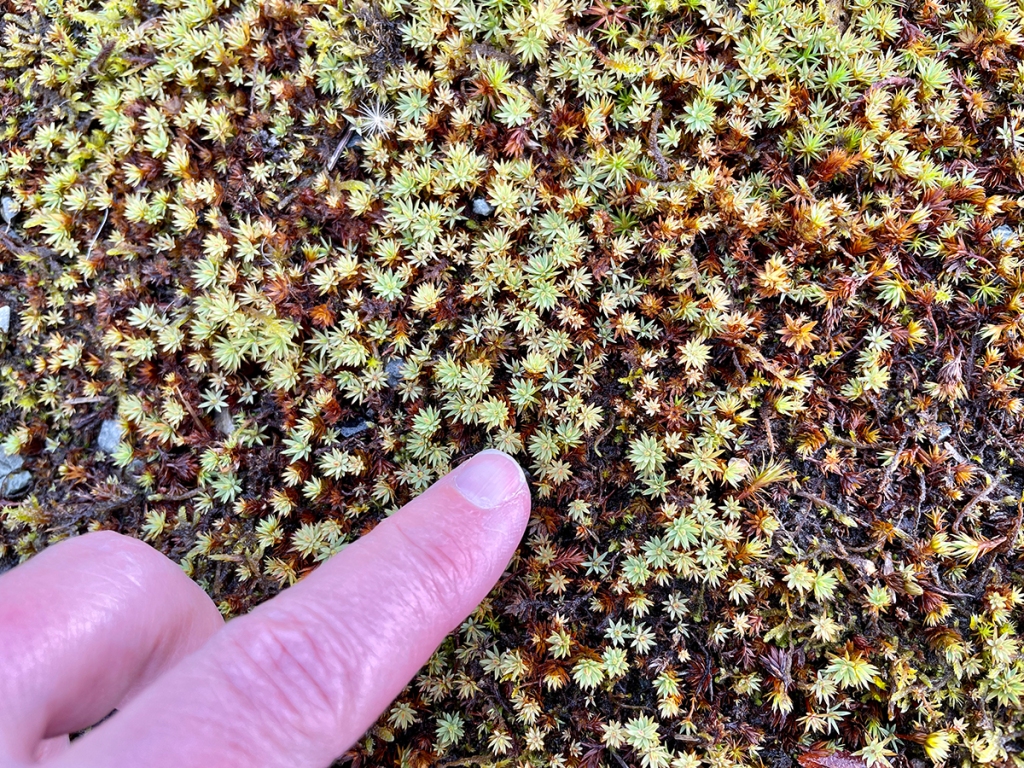

Listening to the watery world of moss with specialist microphones; A tiny (match stick sized) Mycena mushroom grows from the moss in a birch grove near the Braes; and my finger rests on a bed of moss showing the difference in scale. SEE MORE PHOTOS

Why does this even matter? Does it change views, minds, thoughts about what the future might look like? It’s easy to pick a path and be constantly snagged by brambles when you work in the field of environmental arts. Criticism of observations made in the process of thinking about issues and creating new content comes from within creative communities and outside, usually from those who are intensely human-centric, defending an opinion based on their limited experience of the world.

Widening the path

Over my lifetime of living and working in conservative rural communities, those who I should be closest to have remarked or implied that I’m ‘too hard, soft, green, woke, outspoken, opinionated, unforgiving, impractical, unrealistic…’, just ‘too much’. I’ve even been told that I’m too hard to pigeon-hole — as if that’s a problem. I’m prepared to own most of these words, because that’s all they are. All it proves is those people don’t really know who I am or care to. However, given the personal and professional investment I’ve made to ensure the creative enquiry and consultation on projects within my practice of the past decade is as balanced as possible, these ‘tags’ do snag at times. Looking from the outside, beyond my home territories, I don’t doubt the projects I’ve done have had a positive impact — providing opportunity to reconsider what has been heard, seen or understood, offering alternative perspectives or new details previously ignored, and most importantly, giving a voice to the voiceless.

My creative wish list as it currently stands has plenty of brambles to navigate. It’s in no particular order, and I might tweak it going forward, but this is what will continue to drive my work:

- More people involved in the process of creative exploration of the environment, opening ears, eyes, and hearts to other ways of being that aren’t as self-centred, transactional or extractive as they are now.

- Creating more connection points with the natural environments we have left that allow us to experience, connect and value them in new and meaningful ways, even if they’re familiar to us.

- Finding more ways to give the natural world a voice in our care or management of it; a voice that desperately needs agency when human needs still dominate the debate.

- Producing work that reimagines the future as a place of entanglement, where all living things and the landscapes we call home thrive despite the challenges ahead.

- Embracing change and allowing my work to evolve as I continue to enquire, learn, connect and explore.

- Meaningful conversations and co-led collaborations between big-thinking artists and other leaders, influencers and decision-makers in our rural and regional communities, and beyond. We are part of something bigger and we have to step up.

- More time to do all of this through strategic partnerships invested in creative ways of not only raising awareness, but relationship-building, problem-solving, and planning for the future in a way that clear illustrates the alternatives for a better world.

My time on Skye has been about reflecting on my past work and thinking about what the path forward might look like. I’m going to disagree with Russell on the matter of opinions with passion. Without the passion, artists, scientists and advocates fighting for a better world — a richly diverse, equitable, intelligent, healthy, harmonious world fit for humans and more-than-humans — may as well put down our swords. I’m not ready to do that yet.

Addendum

As I shared this post on LinkedIn, I realised two things need to happen to really widen the path for the interdisciplinary work I do. We need governments of all levels to be more supportive of work like this in the regions (less lip service, more doing), and greater commitment by regional organisations and agencies (not just the arts) to be more open to interdisciplinary projects and collaborations. I’m always open to a conversation, but I’m even more open to meaningful partnerships.

******

The watery world of moss, Isle of Skye, 17 August 2023

It’s mid-morning and the day holds promise with clear skies, for now. Dappled sunlight penetrates the shade around the studio and shards of brightness spill across the mossy boulders that are the focus of my explorations today. Using a rubber cap on the base of my hydrophone that converts it into a contact mic, I’m keen to hear the voice of moss. It’s so prevalent here, growing in colonies that over time develop into luxurious, soft green mats covering any solid structure — trees, bricks and boulders, paths, walls, roof tiles, gravel roads and fence posts. I’ve been cataloguing these micro worlds for the past few weeks using a macro lens on my phone.

A line of knee-high boulders marks the boundary of the garden with the croft next door. At one end a cluster of three sit beneath a birch, one is chest-high and covered in scabs of white lichen. One of the lower rocks has a very healthy head of mosses. I sit the hydrophone upright on its surface, start the recorder and step back, the cable resting gently on the edge so as to reduce the chance of unwanted noise. It’s the brittle crackling that first grabs my attention, somewhat like a fire. Beneath the popping and ticking, there are liquid gurgles and trickles. The movement of water through the capillaries of these ancient plants reminds me of the sound of water inside a long garden hose. A small bird calls a measured sw-eet, sw-eet, sw-eet in the branches above.

Only metres away, underneath shrubbery in the deep shade of the garden at the back of the studio, are large pieces of what was once a sizeable tree. They are so encased in moss, I thought they were rock. On one of the stumps, a species of Armillaria, or honey mushroom, are growing in a colony. This pathogenic fungi is known as an insatiable devourer of trees. Their delicate capped fruiting bodies in soft tones of cream and chestnut, are arranged in tight clusters across the moss. The fine filaments or hyphae that mat together beneath the surface, excrete digestive enzymes, breaking down the wood.After taking sample recordings, I use a post-production filter dropping off frequencies below 250 Hz that create a chest-tightening thrum when listening to the raw files. Now, the surface of the mossy stump liquifies into trickling water — a small stream. There are intermittent sloppy slaps, like a wet rubber glove hitting skin. The distorted caw of a jackdaw is caught like a random specimen in the background. Plunging the microphone’s probe into the centre of a clump of Armillaria, below the surface of the decaying wood, the tones within the running water seem to separate into different frequencies — clear, liquid layers reveal themselves. Imagine, putting your hand under a tap of piped water, then grasping the pipe; the liquid reverberates within the log, the stream of sound interrupted by slaps, clicks and squelches.