In late September 2023, eight Walkspace members took part in a micro-residency at the Elan Valley in Wales, the source of Birmingham's drinking water. We undertook our journey in the manner of a pilgrimage, carrying with us a jar of Birmingham tap water to return to its source. We had thought we might respond to themes such as sustenance, displacement and extraction, but Dan Carins soon found there was something else bubbling up. Here Dan reflects on day one of our visit and the walk from Rhayader. This trip was made possible with the support of Elan Links.

We would walk from Rhayader to the bunkhouse not far from the top reservoir of the Elan Valley: approximately eight miles through beautiful Mid Wales countryside. We’d be there by the late afternoon and the others would go on ahead by car with our bags and the food we’d just bought. On a mild, sunny day in late September there would be plenty of daylight – there’d also be a kitchen, hot showers, wine and beds with pillows. There didn’t seem much else to worry about.

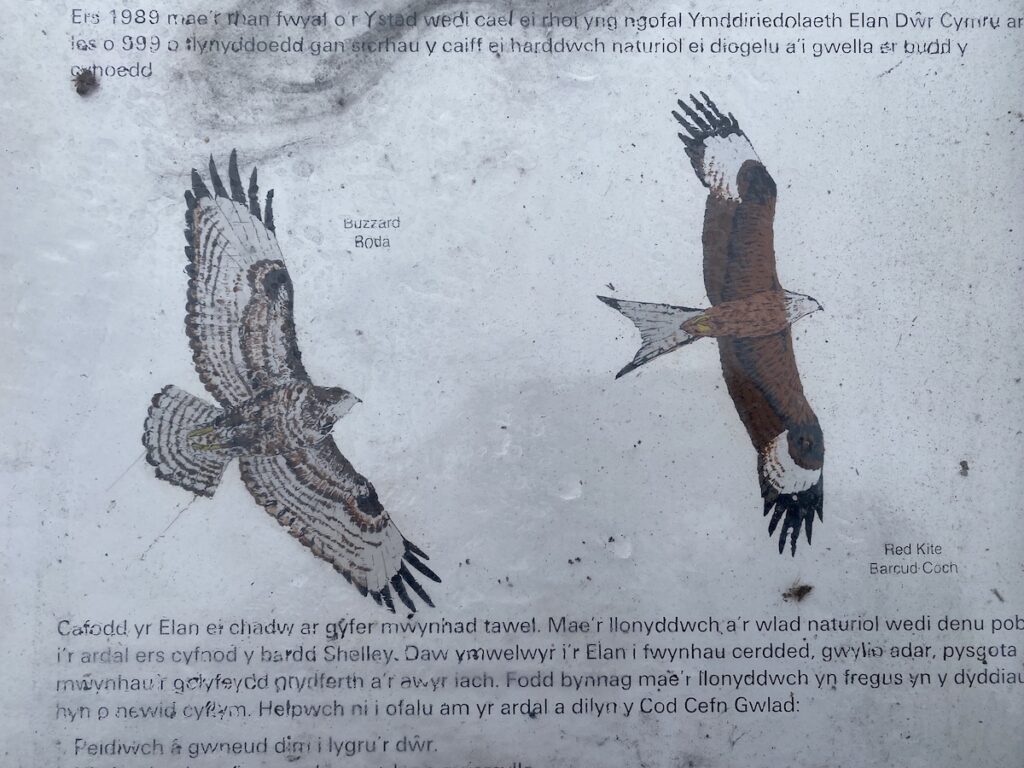

We five follow the path along a disused railway keeping a brisk pace, and we talk. The conversations skip and jump back, finding grooves of common interest among the frequency of observations. We spot a slow worm (or is it a grass snake?), a face in the front of a church made of windows and the door, maybe that’s a kite circling over a field. Someone runs off to take a picture of a river – a proper river! – and to scrump a couple of the largest pears we’ve ever seen. There are giant mushrooms growing on straight, tall trunks. Lambs’ ears growing alongside the path. There are pines – although we can’t agree on which species they are. I opt for Loblolly, only for the word; later I’ll conclude they’re Scots Pines. I say I’ll point one out when I see one.

I don’t see many, and the few that I spot were probably planted ornamentally – they appear at the end of large back gardens of the houses on the edge of town. Pines used to cover Britain from top to toe, but now I associate pines with Greece or Rome, after Respighi no doubt but I distinctly remember being struck by a row of majestic pines, dark green against a brilliant blue Roman morning sky, probably on the way to the forum – unless that’s the name of a TV sitcom that was old when I was young. With the other fruity chap who wasn’t Kenneth Williams. I spot another pine where the former railway disappears into a tunnel. Maybe it grew there naturally, left alone by farmers and protected by the ghosts of a Beeching line.

The halfway point will be the visitor centre at the first reservoir. We head past the car park straight for the dam further along the valley. It’s here we see the first water and begin to piece together the first blocks of understanding the significance of the trip. The valley below the dam wall, the water above it. The scars cut into the rock on the steep valley sides, the bulk of the dam wall. The sluice at the bottom of the dam, the mass of the reservoir behind it. The broadleaf woods we walked past on the valley floor, the firs high up in the hills behind the reservoir. Two old blokes in flat caps talk quietly nearby as they look out across the sun-dappled water.

A couple try to arrange a picnic on a table whilst their young child, wrapped up warm in a pink puffer suit, attempts to gain their attention. She tugs on her dad’s coat as he pours from a flask. The water in the reservoir makes another persistent tug, relentlessly lapping against the top of the dam wall. The sluice thunders below.

From here, it all looks serene and entirely natural: God’s in his heaven – all’s right with the world. Isn’t that Robert Browning? I once set that poem to music: I was proud of it. No – that was Porphyria’s Lover: the preceding poem in my Penguin Poetry Library paperback from 1992. On a plinth, we read the list of numbers and dimensions from the construction of the reservoir and agree that there’s a lot of water behind the dam, and a lot of men and horses moved a lot of earth and stone to build it. We realise we should make a move if we want to keep to our timetable.

I relax more as the walking begins to feel monotonous. We follow a narrow road around the edge of the reservoir, which stretches out far into the distance. The firs I’d seen from the car park have huge scars carved through them: they’re plantations, of course. Suddenly a raven flaps above, making its ridiculous croak: I thought ravens only lived in the Tower of London, and it turns out I’ve been completely wrong for the 12 years since I took my son there. We spot a small white wooden box marked “FISHING RETURNS” on a gate and speculate as to its purpose. There are few people about. Did Fishing ever leave? Who was she? Thoughts like these pop in and out of my head: they’re welcome distractions. I imagine synapses lighting up as we spark from one subject to another.

When I’m walking alone, I find that the more interesting thoughts quickly bubble to the surface once I’ve stopped worrying about work and daily life admin. The same applies when I’m doing the washing up, or cooking – but walking is much more fun. I can make a walk last much longer. Walking in a group doesn’t have the same effect: either there’s no time for the bubbles to rise to the surface, or I remain guarded and awkward. Or: too many ravens. It makes me realise the sheer weight of the daily life admin, and the pervasiveness of my work. I wonder what might have been: what could I have discovered if I hadn’t wasted half my life thinking about employment numbers of now obsolete companies, or how I could have encouraged them to invest? Too late. My brain now feels sluggish, reliant on the vim at the surface of my memory – whatever’s most recent is what sparks my contributions to the conversation. I get by this way. I feel I never dive down deep and really submerge myself these days. It’s probably why I keep talking about the same things, telling the same stories, and mentioning the same books or music or events. There must be some shockers down at the depths.

We approach a bridge that crosses between two reservoirs, past the green cupola of what we call “the plughole”. It’s in the distinctive and unique Birmingham Gothic style, straight out of a Wes Anderson film: not quite British, not quite Austro-Hungarian; not quite fin-de-siecle, not quite anytime else. It reminds me of the Palais de Justice in Brussels, not necessarily because of its style, but more its incongruity: its oddness visible for miles around.

I learn afterwards that this bridge runs atop a submerged dam: it makes sense now, but at the time it simply felt like a footpath built for our convenience: so much infrastructure, so little time to appreciate it. I make a mental note to talk to the others at some point about heuristics, my new reductionist Answer To Everything. On the other side, however, I’m interrupted by a more immediate indicator of what used to be below the water: a small church built to replace the one now submerged on the valley floor. Maybe because it’s slightly elevated from the road, or maybe because it’s a building with a dedicated purpose rather than a more general road. Or maybe because there’s a panel by the road explaining the church’s history. Either way, we stop to ponder and think for a while about what may lie beneath. Apparently, Shelley’s uncle owned a property down there. I think of the plughole, and now this becomes a very tangible and probably very concrete, connection between here and all the way back home. It looks tiny as we begin to walk uphill. It’s covered in a metal grille.

I start to think about the monsters in that Douglas Adams novel that think if they close their eyes, they can’t be seen. Which book was it? What were they called? I hate the way my brain instantly tries to shut down gaps in detail and memory, rather than focus on the problem in hand. I’m worried about what lies beneath, not about The Restaurant at the End of the Universe. Bingo! That’s the one. If we can’t see a submerged church, is it still there? Is it still a church? What was lost – for them, or for us? I see a reservoir below me. Before, it wasn’t there, and instead people would have seen a wooded valley either side of a river. Would they have had the same thoughts? Or would they be thinking about getting to church on time, and whether their bonnet was fastened securely enough? We don’t think much about what might have been, but we think a lot about what might be: ask anyone objecting to a planning application for new houses on greenbelt who lives in a house that was built on greenbelt. Ask National Trust members: preserving a particular point in history, rather than what was there before it. It’s called loss aversion – finding a £ in the underground generates less excitement than the annoyance we feel when we lose a £. We keep walking, and I keep my eyes peeled for pine trees.

We speak about the project we’ve been asked to complete. I’m minded to prepare some drawings of the reservoirs and dams. Only, drawing water is incredibly difficult. Drawing moving water sounds impossible, especially since my drawing skills don’t extend far beyond buildings and trees. I think about inserting drawings of cross-sections into a model valley made from card, to create a sense of movement, place and scale. This quickly turns into a simple V-shaped structure once I realise how difficult making a paper model of a valley will be. I’ll worry about the purpose later: for now, I’m eager to think of what I can draw.

Pine trees feature highly, but I need broad vistas. I scout the horizon. I’m grateful for this: before I started drawing, I would look around, and up, but I’d be looking for the economics, the human geography. I’d be looking for the implications of public policy on the built environment. I’d be looking because of my work. Whilst interesting, it also feels remarkably limiting – or futile. So what if I notice the layouts of factories along the Colne Valley, or observe the customers of retail outlets in North Norfolk? They might help me relate to someone at an event or talking to consultants. But ultimately, no one cares. Meanwhile, I’m not paying attention to whoever I’m with because I’m too busy noticing the flows of stock or material, and observing people spending money they don’t have. Starting to draw gave me a different incentive to pay the same attention to detail, but with a far more modest and practical purpose: subject matter for sketches. At this point I’m less interested in aesthetics and composition, and more about whether I have the technical skill to draw places faithfully enough to resemble the real thing.

And so I look. After a while, it stops me thinking. And when I stop thinking, more thoughts rise to the surface. Different thoughts. Thoughts that were lying further beneath the surface and which haven’t seen the light of day for a long time. These in turn, give me new perspectives on what I’m looking at, which generate novel thoughts. There must be an awful lot buried down there.

I’ve been reading about how stress and trauma can alter the shape and form of our brains as we learn to obfuscate, ignore memories and associations, and try to skirt around the past or to ignore it altogether. What was past is past – how we remember it is plastic, as are our brains. We assume that the past is singular: that fact is fact, truth is truth and history is history, like we think time is precise and measurable against a universal constant. But if our brains change shape and form, then so must our memories, and so must our pasts.

Is their knocking relentless, those memories against my skull, but so quiet I don’t notice? Or do they remain silent, waiting to be unearthed? It often strikes me how memories can appear so suddenly, apropos of nothing – or so it seems. Had the “so it seems” always been there, a frantic semaphore, desperate to bag my attention? For how long? Does it get tired? Or had it in turn been triggered by something else? Do we knock holes into our brains by repeatedly ignoring memories: like the shapes eroded into tree canopies by dozens of buses passing each day – we grind them down until they disappear. But their outline will give them away, like how rain won’t fall underneath a man wearing a cloak of invisibility.

I’m sure dreams operate in a similar way: we create our dreams after we wake, grabbing memories from whatever is near at hand. This to me explains why some people’s dreams, when they recount them, last for ages: it strikes me as implausible that people were dreaming for this long. The silence of the surroundings lulls more and more memories from the depths as I walk. We’ve grown quieter now: possibly increasingly anxious of the lateness of the afternoon and how much further we still have to walk; possibly due to the seemingly endless stretch of regimented fir trees (they’re not Scots Pines, that much I know) creaking alarmingly in the breeze.

The reservoir narrows on our left as we continue. It’s not far now. I think of the volume of the water, the force this must exert on the dam walls, the calculations required, and the compasses and slide rules the clerks and engineers must have used in stuffy, gaslit offices back in Birmingham. Weight and mass and volume. Resistance. All of which must equal an opposite force = a lot of stone hewn from the valley walls, a lot of navvies and horses hewn from villages and towns. That gentle lapping now feels more mechanical: did they calculate for erosion and decay? How long will the dams endure?

We spot the others coming by car the other way. We realise how long we’ve been taking, and how bored they must be waiting for us: they’re off to try some bouldering. They tell us it’s only around the corner. My arthritic toe hurts.

I have a sense of what lies beneath. Or rather, I have a sense there must be something below the surface. I know there are leaks which erupt now and again. I know I have triggers, and I know there are topics of conversation that are taboo or make me tense. Maybe I was too young. Maybe I’ve created monsters that aren’t there, for lack of anything interesting to say. I think again of the grille covering that plughole, and of the void behind it: 70 miles of slime-covered pipes drawn up by dusty Leonard Bast clerks taking the water to my taps, or the black hole of trauma. Which could it be?

It turns out to be much further than “around the corner”, but we eventually arrive at the bunkhouse long before the sun sets. We cook. We eat. We sleep. We talk some more. Over the next day, those dam walls get bigger and bigger the further and further we walk up the valley.