I was running late to meet Bill and stuck underground. As I hurried out of the station, worried that he might have given up on me, I spotted him at a distance. Though I had never met him before, there was something about the way he was standing; it was the look of someone waiting to walk.

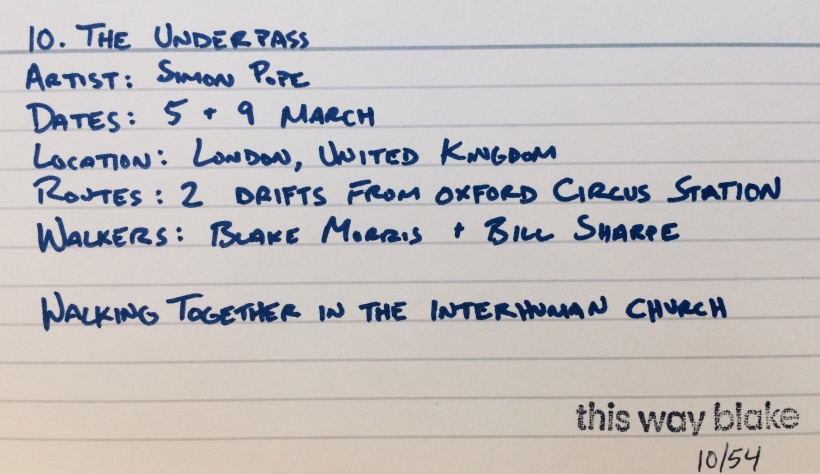

Bill and I were meeting to embark on Simon Pope’s The Underpass, a walking score that favours ‘chance and gameplay over utility and purpose.’ We filed into Oxford Circus station with the commuting masses, ignoring the free Evening Standard’s being offered—Bill commented that they cost money when he lived here in the seventies—as we descended underground. Pope’s score requires a tube exit map and a few calculations: the highest numbered exit (4), minus the lowest numbered exit (2), equals the exit of departure (3). Having completed the necessary maths we found exit three and began.

Bill, known professionally as Professor Sharpe, is a visiting Fulbright scholar from Barnard University. ‘What is walking art?’, he asked early into our walk. Indeed, this is his current research question. A professor of literature since 1983, Sharpe has long dealt with characters who walk. But what about the walk itself?

Walking art, I argued, was what we were doing right now: going on a walk designed by an artist. Despite Hamish Fulton and Richard Long’s reputations as ‘the archetypal “walking artists” (Pope, 2014, p. 16), their work primarily represents their experience of walking. The medium of walking, rather, is defined by the action of going for a walk. We were walking one of fifty-four scores into existence as part of a ‘global season of walks‘.

We circled the Circus, always ending up at the same places: the station, Regent Street, Piccadilly Circus, Regent Street, Piccadilly Circus, Carnaby Street. Put on a blindfold and you walk in circles. This was not the same sort of attention to place I had earlier experienced while walking in circles. It was a panopticon without the performance or the paranoia. A social drift through a shopping vortex. We barely noticed the specifics of the shops, consumed instead with each other, our memories and the general layout of the built environment. For me and Bill, not shopping Oxford Street was not a dropping of our everyday relations; rather, it was a continuation of them. Like many with whom I walk, ignoring the shops is not a problem. Why shop the High Street anyway, when Amazon is primed to bring it to your door?

A few days later I revisited Oxford Circus on my own. Off the tube to the exit map: the highest numbered exit (7), minus the lowest numbered exit (5), equals the exit of departure (2). No access to exit two. Up the stairs to the street and down another entrance. I locate exit 2. Closed. Exit 1 it is then.

The solo dérive is unspectacular. It begins with a lack. An inability to go through the recommended exit. Though ‘one can dérive alone’, Debord (1958) recommends groups of two or three. Above all, the dérive is social; it brings walkers into the directly lived moment together. It builds unmediated social relations. With Bill I was a drifter; alone a flâneur. I walked an imaginary turtle against the grain, hoping it wouldn’t be crushed under the gilded weight of city traffic.

As Pope (op. cit., p. 19) notes, ‘[w]alking alongside becomes a means to negotiate a flow—of conversation, of movement.’ It ‘becomes symbolic of an ideal type of relation’, one with ‘the potential for mutuality, parity, or equality.’ The walk is a vehicle for relations. So what happens when I walk alone? Or was I alone? Wasn’t I walking with Pope? It was his design after all. As I walked I thought of an essay I had read by Samuel R. Delany; Delany wrote that as long as we have language we are never alone—the developments of human history accompany and guide us. At least I think he said something like that, I never have been able to track down a quote. A ghost of a quote, haunting my memory. I thought of Proust whose narrator discovers in Time Regained that the two walks he always considered opposed ‘were not as irreconcilable as [he] had supposed’ (1981, pp. 5270-5271). So I walked alone, but my solo drift was haunted by Pope and Delany, Sharpe and Proust. A ghostly fraternity with just enough queers to keep it interesting. Perhaps alone and together aren’t so irreconcilable as I had once supposed.

I approached the same points I had with Bill from a different perspective—I was consciously seeking different circles. I thought of my walk a few weeks earlier, in which I created an exquisite corpse with my father and niece. Upon unveiling the full text differences in perspective were laid bare. One section read,

Respect for the flag is not submission, it is an acknowledgement that we have been granted the right through ever changing laws to protest what we think is wrong/Celebrating great men.

My father and I have different understandings of American exceptionalism and my immediate reaction to this line was discomfort. This friction, however, is part of what the walk can offer. A location for mutuality—even when viewpoints diverge. Indeed, the crux of my father’s sentiment is his belief in my freedom to express this discomfort. The right to dissent is an American ideal on which we can both agree. Of course parity is a prerequisite for mutuality… perhaps it should come first on Pope’s list.

As I finished my walk and headed towards Soho, another queer haunted my steps: Witold Gombrowicz. ‘[P]eople create themselves mutually’, he wrote. We are interdependent, in a ‘constant creative bond with others, permeating them through and through, dictating the most “personal” feeling’ (2012, p. 579). This ‘interhuman church’ can be found in the art of walking, which asks us to take time together to forge a creative bond. Perhaps that is the point after all: on an artists’ walk we are always walking together, even if we are walking alone.

One thought on “”