Weird Walk is a zine in the true sense of the word. Sure, it’s an A5 publication of 40-odd pages that you get in the post, but it’s also a collection words and pictures about a thing that the authors are obsessed with and which they need to put in a package to send into the world, hoping it reaches others who are equally obsessed with said thing. A zine, in other words. And in an era of zines-in-name-only (don’t get me started) it’s refreshing to see a real one.

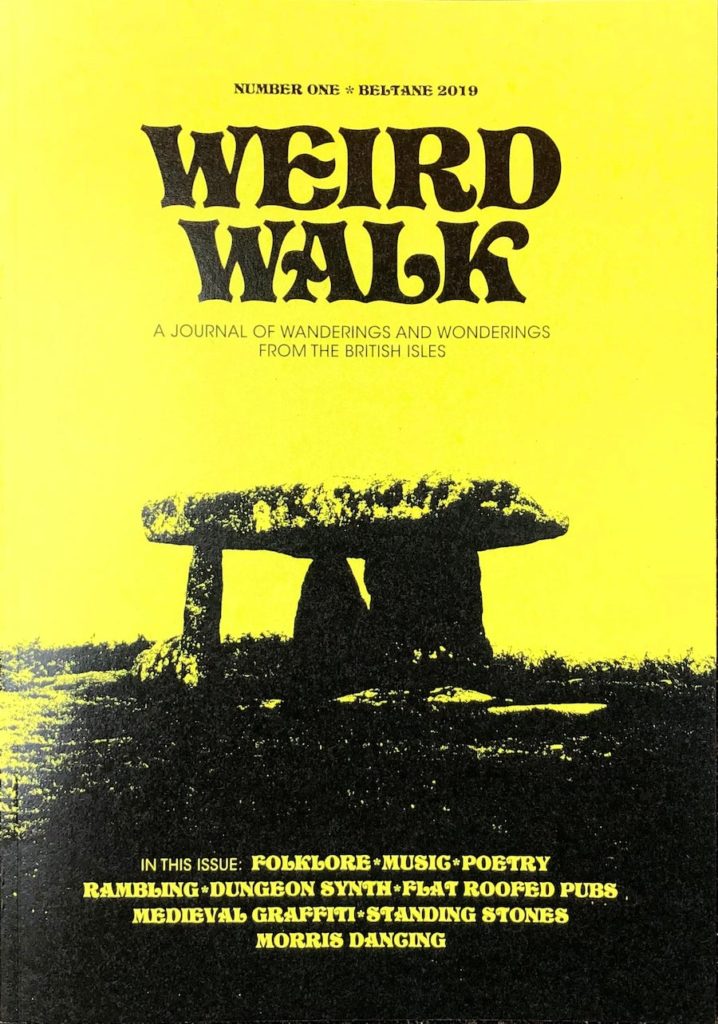

Weird Walk is about walking, obviously, and the stone dolmen on the cover, not to mention the typeface, indicates an interest in the old and ancient. Heading the editorial introduction is Julian Cope quote from his Modern Antiquarian period which pulls us away from traditional heritage and focusses us on a more contemporary take on the old, a revivalism of the pre-modern, looking far, far back for something, anything, that might save us from the eternal now of regurgitated pop-culture nostalgia. A search for something weird.

This idea of the New Weird has been bubbling around for a few years. John Doran of music/culture site The Quietus coined the phrase New Weird Britain as a bucket for all the acts he was seeing at gigs and festivals that didn’t fit into the music industry but also weren’t really part of the art world. Freaks and weirdos doing their thing because they needed to. He wrote a nice introduction to the concept for the BBC and themed The Quietus’ guide to Birmingham’s Supersonic Festival around it. Notably, however, New Weird Britain isn’t a unifying sound or genre. You will find stuff that sounds like folk music in the NWB bucket – Richard Dawson springs to mind – but that’s not why it’s in there. It’s more about being outside of the mainstream, but not in a tedious rebellious way. Less punk, more WTF.

When the New Weird crops up in movies the aesthetic is much more focussed. Paul Wright’s Arcadia, a feature formed from 100 years of archive footage, leans hard into Weird Britannia, joining up ancient pagan rituals with 20th century non-comformity. It’s a celebration of that which the Victorians and Modernists found horrific, but whose attempts to remove it from British identity left an urban, post-colonial Britain unmoored.

I always find it quite telling that, according to the horror tropes, we’re supposed to root for the Edward Woodward’s policeman in The Wicker Man but modern audiences are all about the islanders. Summerisle is no longer a heathen backwater but a utopia that has escaped the futility of the modern world. We want to follow Christopher Lee’s Lord Summerisle, to sing songs and copulate in the fields and burn Christians.

For contemporary movies I always think of Amy Jump and Ben Wheatley’s A Field In England as epitomising the New Weird. This story of four civil war deserters tripping balls in a mushroom-infested 17th century field bypasses heritage period drama, neatly sidesteps Monty Python absurdity and barely nods at Hammer Horror. It seems to be reaching for something older, something Shakespeare or Chaucer might have struggled to reach. The hallucinogenic mycelium threading this field brings the soldiers into contact with a land so vast and unknowable it’s closer to a Lovecraftian void. Britain is old. So old that even people in olden tymes could get lost in it.

English identity is a particularly fraught thing to go in search of, particularly when you associate it with the land. Richard Smyth’s article on Nature Writing’s Fascist Roots is a cautionary tale for those who would seek answers in England’s green and pleasant land. When we talk of the land we think of the countryside and forget that villages and farms are as “natural” as an urban factory and just as infused with class and race inequality, if not more so. In navigating this the weird is a helpful guide. When confronted by an idealisation of England, does it make you feel comfortable? Or does it seem a bit weird? Always go with the weird.

In the introduction to his epic survey of 1970s esoterica, High Weirdness, Erik Davis spends a while unpicking the word and its many applications through history. This bit on “weird naturalism” felt relevant.

Most of us have had experiences that, unless we have utterly misread them, put severe pressure on conventional realistic accounts of how the world works. We may have had a prophetic dream, or been struck by an absurdly recurrent synchronicity, or received advice from a forest creature, or glimpsed a bizarre object in the sky, or felt the presence of a loved one at the time of their distant death. Or we know people who report such experiences in ways we have no reason to disbelieve. If we want to earnestly describe such experiences without rejecting common-sense realism, we reach for the language of the weird. “I know it sounds totally weird but…” or “Pretty weird, huh?”

Why do we do this? One reason is that to characterize a phenomenon or object as “weird” is to sneak in no extra metaphysical claims; no divine writ or occult rumor is needed to vouchsafe the existence of strange and uncanny impressions or experiences. They are part of human life, at least if you are paying attention. At the same time, the weird does announce the appearance of something like anomaly, or at least deviancy—inexplicable, aberrant, or unsettling events or encounters that pull or twist against the norm. Statistically, such deviations may be perfectly routine. But they never feel that way. So we don’t know where to put them. Many of us forget such events, or sweep them under the carpet. And by using the label weird, we acknowledge them, but also trivialize them. The weird twists the profound depths it seems to point to into banal, even throwaway, surfaces.

High Weirdness, p8

The weird is the bucket we put things in that don’t make sense but don’t really matter. Once that bucket fills up and overflows, maybe we should start looking at it.

Weird Walk is a zine about walking. It has photos of prehistoric standing stones and Tudor woodcut figures. The typeface evokes a 70s hippy publication found in an Avebury cafe. Other than a feature on a suburban pub east of Birmingham, its content is firmly beyond the city. It’s a zine in search of something old, something from before. Something weird.

After invoking the arch-drood Julian Cope our editors ask “What is a Weird Walk?”

For us, walking is an active engagement with the British landscape and its lore. Whether traversing the chalk paths of the South Downs, or the shifting landscape of the Black Mountains we want to not just stretch the legs but also get thinking and talking and creating around the land and its history, both real and imagined.

Which strikes me as an admirable refusal to define the weird! You know it when you see it, and when you see it you put it in your zine.

The two main pieces in the first issue are interviews and mark out the boundaries of Weird Walking quite nicely.

Justin Hopper is quickly established as the spiritual father of this enterprise with his book The Old Weird Albion serving as a touchstone for the zine. An exploration of the South Downs, I was struck by how he approaches his walking as someone disconnected from the land. Like myself, he had a rootless upbringing, not really being “from” anywhere specific. So when his grandmother took him on walks he was like a sponge, ready to be “part of something old and wise”. The familiar is the enemy of understanding. To really see something it helps for it to be strange, beyond our everyday understanding. It’s an understandable irony that the rootless are the ones who best see the roots.

The other interview is with Matthew Champion of The Norfolk Medieval Graffiti Survey who leads a growing community of amateur historians looking for ancient markings in churches and other surviving buildings. He sees these scratched symbols as a link to all levels of medieval society, not just the priests and nobility. They also tell us about how people related to these buildings in an active way, physically manifesting their prayers with markings. Indeed, leaving a mark only became frowned upon in the Victorian era. It was seen as an acceptable way of communing with god, to leave your mark in his house.

These two interviews give a necessary depth to the Weird Walk venture, anchoring and contextualising the relatively fluffy zine-staples like music reviews and the obligatory poetry page. A two page history of William Kempe, the Shakespearian comic actor who undertook a 100 mile morris dance from London to Norwich, takes on a new pathos in this context. Kicked out of the theatre for his anarchic tomfoolery he embarked on his long dance across the land, embraced by the public and imbibing of much ale. But within three years he had died in poverty and obscurity. The English Renaissance had no place for his medieval pagan nonsense.

Kempe makes for a worthy icon of the weird walk because he was there when the sensible really started to kick in. Let us walk in his shoes and imagine a different, weirder world.

Weird Walk issues 1 and 2 cost £5.50 each plus postage and can be ordered from weirdwalk.co.uk.

This review covers the first issue. I’m saving the second for later, once I’ve properly digested this one.