With The (Future) Wales Coast Path, Alison Neighbour, through a cooperation between Wales and India, Alison Neighbour seeks to raise awareness of the impermanence of the land many of us take for granted, and to open up a local and global conversation about flooding, sea level rise, and adaptation.

This walking piece is one of the shortlisted pieces in the Marŝarto Awards 2023. Here, Alison discusses her work.

Let’s go slowly, like a wave… our lanterns raise and dip as we walk.

Slowly, almost imperceptibly, the tide creeps inwards, no beginning, no end, a continuous cycle of replenishment.

Some say the sea begins in the raindrops, that each raindrop is a bit of the sea.

During the walk it drizzles a little, giving everything that soft blurry dampness. We are hopeful of a sunset but are rewarded with only a milky pink glow.

Puddles fill the track. Splashy, splashy, sea on our feet.

Later that evening, outside the open kitchen door, the rain begins in earnest, a soft sound in the trees at first, punctuated by the heavy thud of an end of season apple falling.

Then louder, drowning out the call of an owl, as the cycle resets and sea falls from the sky…

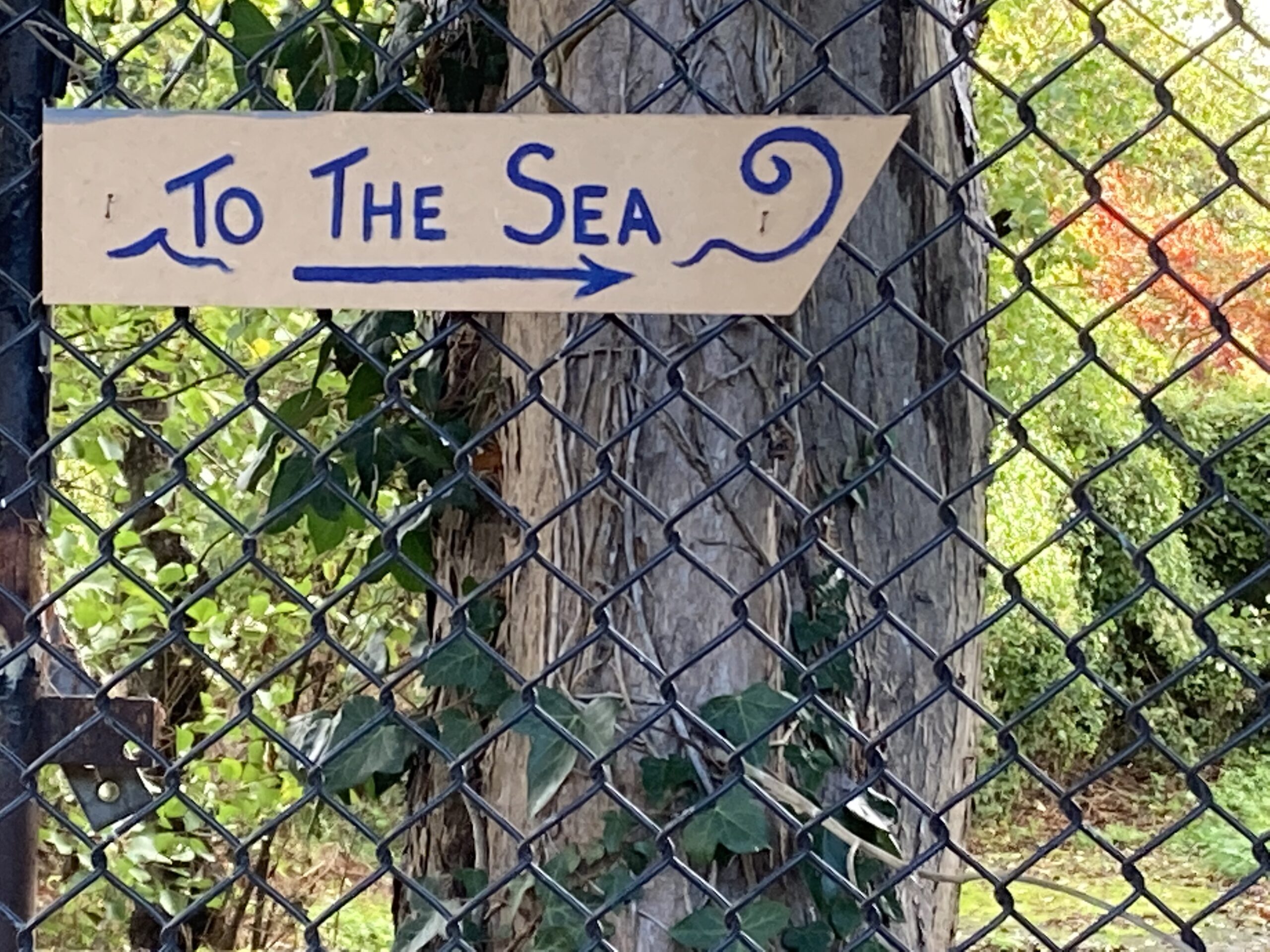

Our last walk to the seawall in Autumn 2022 saw our regular little crowd joined by a excited group of local Brownies – around 50 of us made the pilgrimage from the village to the sea and back, carrying our homemade lanterns to light the passage the sea will take in the future, when it eventually tops the seawall and flows down towards the homes and farms. On Sagar Island the weekend before, a similar procession had made its way on the (increasingly shorter) journey from the beach to the village, marking in light their present intertidal space and a warning for our future. The conclusion to a year of walking that had a profound impact on all of us who made the journey.

In the UK we began in heavy boots, wrapped up against the cold and ready for mud and flooded lanes. Later we walked in sandals, foraging for berries, apples, plums, and samphire as we made a rare foray onto the foreshore to take advantage of the low summer tides and dryness underfoot, plus the samphire- a special treasure brought by salt marsh, a luxury for us and available only to intrepid foragers who know the tides, it was common food for our ancestors. By the end of the year we were back in our boots and the “Free Apples” sign was back outside the first house on the road, as it had been on our very first walk. We observed and noticed the changes in the landscape as we journeyed together to the edges of where sea meets land – a slightly different point each time we made the trip. We looked at this familiar landscape on our regular walks each time seeing something new.

In India the sense of loss was palpable, teenage walkers shared films of themselves singing on the ruins of their primary school, now buried under the sand and sea; we saw the temple in its new location, having been relocated seven times in not many more years; we walked with them over a broken section of the seawall, aesthetically so similar to ours, made of mud and sweat and hoping for the best. Instead of a cycle their year felt like a line- a line that was gradually shrinking the island, exchanging land for sea at a rate we could not imagine. And yet, for the walkers there this was their life – they did not speak of climate change as some distant future, for this was their every day and it had to be managed.

The sea is comfortable with change; each day a different light, a different height, a different shape. How does such a volume of water move in such a short space of time? Transforming land into sea and back to land again in an endless cycle of shift and change, a cycle that we too are part of, as we navigate how we can continue to live on this fragile landscape and we question what the future holds. What can we learn from this? How can we embrace this cycle, not to “use” it, but to exist better within it?

Where we might speak of the future, others live this reality in the present

Many of us around the world are coming to terms with the idea that land and sea are not fixed entities, but shape shifters, in a constant process of exchange. In this walking project we aimed to come together as friends to better understand this process and our part in it, meeting a community on Sagar Island who were experts in what we may face and opening a conversation between our two lands through walking together across time and place. The sea does not have borders and boundaries – the water that laps on our shores has touched many others as it ebbs and flows around the world, sometimes supporting livelihoods, sometimes swallowing homes and farms. The reality of this hit home on our walks. This was not about “them” (whoever “they” are), this was about us – all of us. And about me – my home, my familiar land, my memories, my history. If all this were gone, where would I call home? What would home be?

We tried to fix these walks, these conversations in guidebooks, fixing a place in time whilst inviting new walkers to embark on their own voyage of discovery through a document of the collective conversations and imaginings from walks undertaken and maps made within the future (and past) intertidal space of the Gwent Levels and Indian island of Sagar throughout an annual cycle in 2022; as an invitation for future explorations on impermanent land. Perhaps you too will search for where the sea begins…

The (Future) Wales Coast Path is an arts project that confronts the global crisis of sea level rise and asks where we might go from here. It took the form of a year long series of community focussed creative walks by me, artist Alison Neighbour, exploring our relationship to land and sea and what we might do to protect our fragile landscape for future generations. The centre-piece of the project were Lighthouses on Magor Marsh and in Newport town centre, in Wales. The solar powered light connected via global tidal data systems to a buoy in the Bay of Bengal and flashed when the tide was rising there, bringing us together with global communities to consider what it means to live on low lying land.

In India, walks were led by Vikram Iyengar and colleagues, and walkers in both countries took part in an exchange of words and photographs, documenting their discoveries on impermanent land. Throughout the project, walkers were invited to respond to the question “Where does the Sea begin?”

The winners and honourable mentions of the Marŝarto Awards 2023 will be announced in February 2024.