The approach to a new year is conventionally considered a time for reflection and resolution. The period between Boxing Day and New Year’s Eve (sometimes irritatingly-appealingly referred to as ‘Betwixtmas’) is when I typically do most of this sort of thinking in a fug of cheese-related shame and satisfaction. One thing I perhaps ought to resolve is to keep my self-imposed writing deadlines; this post, the purpose of which was to introduce myself as Walk-Listen-Create’s poet in residence for 2023-4, was due over a month ago. Unfortunately, what I like to call my ‘work-work balance’ –between teaching English at a secondary school, writing a PhD, and occasionally submitting poems to things– often leaves very little room, even for the privilege of banging on about myself in prose. I’m glad to be doing it now, though, and pleased to meet you, if you’re reading this.

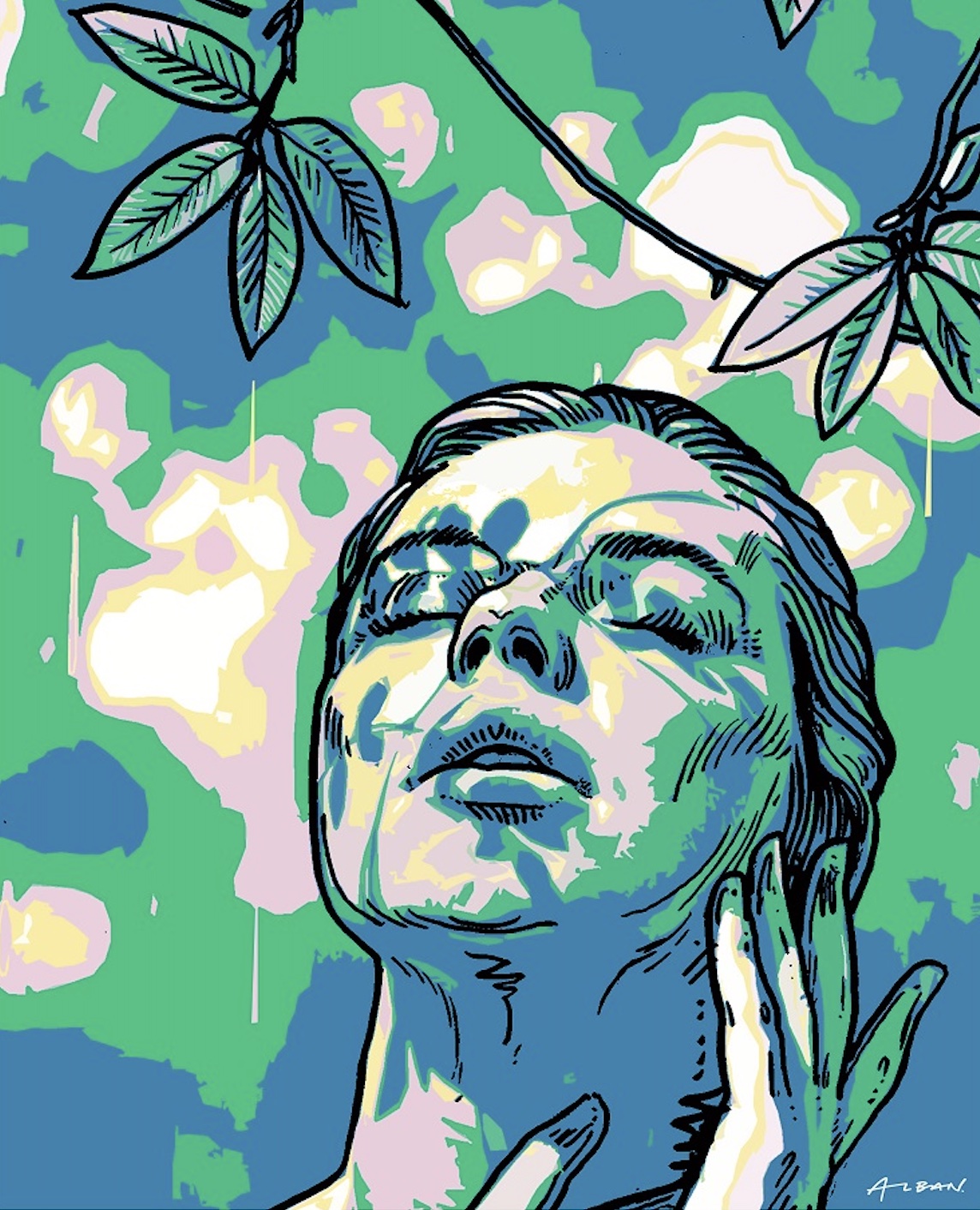

A great deal of my creative work, as well as my PhD project, concerns the natural world, especially trees and the ways in which humans relate to them. I love this time of year because of how local nature appears to confirm my preference for wandering around in a forgiving jumper, thinking about the difficult and unlikely new habits I might try to pick up in January. Southeast London’s planes and ginkgos and limes and sweetgums are bare or sleepy, unhurriedly gathering reserves to begin their spring emergence. The air is misty, lending vagueness to everything around, as if to say, ‘it’s fine if you’re just spending a bit of time working things out’. I may sound sceptical about New Year’s Resolutions (and with good reason given my track record), but the impulse to get myself slowly together for the spring feels like one that I’m picking up intuitively from observing the trees. A slow and complex growth, blossoming occasionally, seems like a metaphor of self-improvement I can embrace.

The title of this post, ‘Hope You Like the New Me’, is that of a track from Richard Thompson’s 1999 album, ‘Mock Tudor’. The song is actually a bitter denunciation of a treacherous ‘friend’, containing lyrics like, ‘I stole your style, hope you don’t mind/I must try to be all I can be/It suits me more than it ever suited you/Hope you like the new me’. It goes on painfully to highlight the cruel self-serving of such identity-plagiarists– ‘Feel free to lean on me/But please, don’t do it right now/Yes, I’m much too busy right now’. It’s more a song about betrayal than self-improvement, but this resolution-filled time of year, with its language of erasure and becoming ‘new’, often makes me think of it, and serves to warn against a regeneration whose basis is in disingenuousness or appropriative disloyalty.

This year, Thompson’s lyric also makes me think about our relationship to our environment: human consumption, especially around Christmas, is destructively rapacious. If I take my metaphorical cues from London’s trees as we approach the new year, perhaps I owe them something back, or, like the song’s speaker, I risk becoming a ‘New Me’ at their expense. Eliza Cook, a nineteenth-century working-class poet from South London whose works form part of my research, writes about the ‘debt’ owed by humans to trees, presenting working people in a sort of solidarity with nature. Thanks to writers such as Peter Wohlleben, we now know that forests themselves demonstrate what humans might call solidarity with one another– maintaining sick or weak trees and felled stumps through fungal root networks. These ideas inspire me to a different type of commitment than the traditional resolution: my work may reach only a few already-willing ears; my choices as a consumer may only have a minor impact compared to the billionaires and corporations who could really affect climate change; my actions as an individual may make me appear to be a naïve sucker. But, if I am to improve myself, it has to be through the intricate building of tiny networks of solidarity, through the gradual growth of new green, through the slow sky-reach of effort.

So, if I have one resolution this year, it is this: to Be More Tree.