With walkingwhiledrawing * Parnidis Dune, Janice Jensen created highly individual perspectives on the world around her.

This walking piece is one of the shortlisted pieces in the Marŝarto Awards 2023. Here, Janice discusses her work.

When I travel to places I have been before I find it interesting to notice that being at certain spots brings back memories that I had forgotten, prompting me to remember routes that I used to walk. This makes me reflect on a persons perception of a place and how they navigate through it, is made up of many individual signifiers which are visually and spatially personal. So, I wanted to explore which individual parameters influence my orientation and why I am attracted to certain things whilst overlooking others and how I process my surrounding when moving through it.

The tendency of cartography to organize places in a system with a determined meaning felt strange to me when contrasting it to the experience of moving through the same places and seeing them constantly transforming. When defining surroundings as a map, there is no need to take a closer look, to search and find, to try and leave things open, they are an efficient tool. I understand why maps can be useful in some ways, but also they make us look at the map instead of looking at where we are.

With these thoughts in mind I started to work on my project walkingwhiledrawing in 2021 when I spent an Erasmus semester at Vilnius Art Academy. I planned to use the situation of being at an unfamiliar place to find a method to translate my subjective perception of moving through my surroundings into something more visible.

I was interested in experimenting with recalling and recording my movements whilst walking and experiencing an environment. Initially I was relying on my memory of various walks and basing my drawing practice by focusing on recalling the route. I decided to draw my immediate reaction to the surrounding during walking. That way I would be able to represent my selective view but also the moment of passing by and movement through the surroundings itself.

In order to be able to draw while moving I designed a drawing machine that allows me to draw while walking without being interrupted by having to constantly flip through the pages of a sketchbook. I connected two rollers on a wooden board and inserted a paper scroll between them. The paper then can be scrolled with a knob which is screwed to one of the rollers. The paper scrolls measured around two meters and depending on the speed of drawing and walking can last up to ten minutes by drawing, turning the paper and walking simultaneously. I found it best to keep a steady rhythm of turning, walking, looking and drawing, to be able to fully concentrate on the surroundings and not interrupt the performance.

Although the drawing should be impulsive, it was initially quite challenging to deal with the many micro decisions such as deciding on the present features, the self control of leaving things unfinished which have passed by already, and depicting only the rough shapes without going too much into detail. The act of drawing and walking demands focusing entirely on the practice itself, drawing and looking melt into one action and drawing turns in into a recording method where one can find a lot of surprising details on the record when looking at it after it has been made. Although the drawing scrolls are an important piece of documentation, they were in many ways merely a linear documentation which did not provide a sense space and movement.

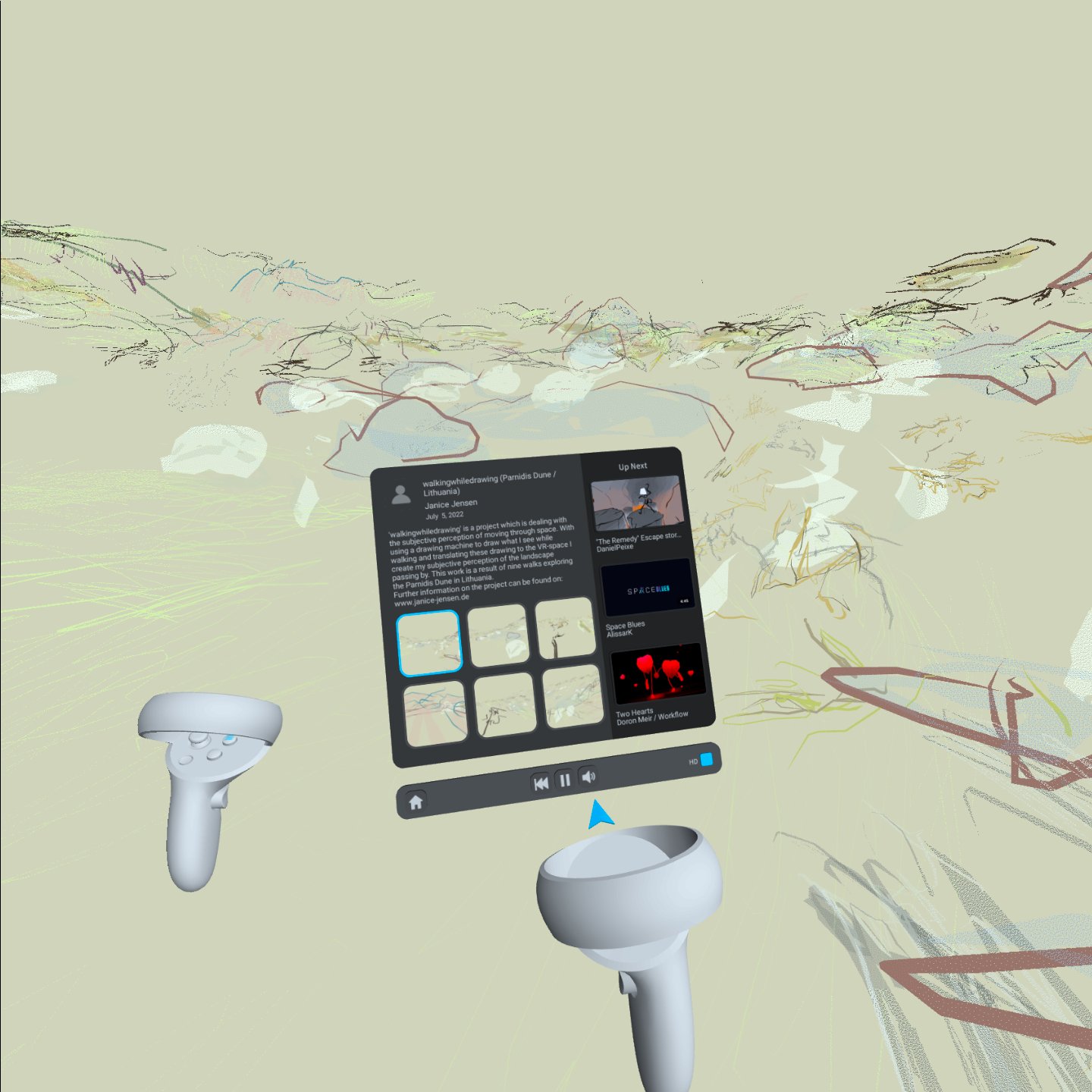

When searching for other approaches that bring back the movement of walking through moving spaces, I started working with virtual painting to translate my drawings into virtual landscapes that can then be explored with VR goggles. That way I could create an open entry into my drawing, as the VR landscape has no set directions and also make it possible to move within the drawing.

My first virtual landscape was made at the Curonian spit of Lithuania, in one of its shifting dunes called Parnidis in Nida. The area I documented is a basin which is enclosed by sand hills. Walking in the basin felt like being in a desert, there were long furrows drawn in the sand by the wind, a little bit of grass and plants and dry branches. As soon as I would walk on the top of the dunes I could see the forest, more dunes and the sea.

The diameter of the oval area that I was researching measured around 86 meters. I made nine different walks, each focusing on specific landscape features and using different drawing mediums such as charcoal and pencil which best suited the features I was recording. The themes of the walks were the outlines of the dunes, their physicality and shape or the patterns of the sand drifts as the topography of where I was walking.

As I did not plan my walks beforehand, I traced them with GPS to have a reference for my recreation in VR afterwards. However, tracing my GPS only describes the position where I was located, but not what I was looking at. I often found it necessary to control my sight by only looking in one direction and focusing on a certain distance, comparable to sharpening a camera lens to ensure a correct sense of scale.

Anyways, I kept this method open to be used as I still wanted to react impulsively on my surroundings.

To transport my walks into VR I scanned my analogue drawing scrolls, tracing and repainting each line in VR and arranging them as 3D objects, placing the lines in the VR environment. That way they could only be recognized when looking at them from the same angle and perspective that I was observing them from when drawing with the drawing machine. The process of translating the 2D drawings into a 3D object brought back my memory of what the abstracted shapes I was drawing beforehand were representing and also made me understand their spatial order and scale.

After allocating all nine walks in the VR space I found places which overlapped which were showing the same objects but from different perspectives as they appeared on several walks while others would only be defined by one drawing.

The entire VR landscape thus became a collage of fragmented moments, every drawing representing a unique record of the passing surrounding which can not be repeated. This whole becomes an ongoing process, and so is the walking person, and if they meet it is an interaction instead of an observation. If I would repeat the project at the same spot I would create a different landscape, none of them would be more true than the other as they both don’t aim to represent the Parnidnis Dune in Nida but walking and looking at it.

As an observer with the VR goggles it is possible to walk a distance of up to ten meters and in the Parnidis Dune VR- landscape it is possible to teleport oneself to six different spots from where one can explore the surroundings.

Additionally, I created eight films which follow the traced reconstruction of each walk that I made in VR by cutting out the rest of the VR-landscape.

When watching them, the drawings can be reassigned to the analogue drawings scrolls which I also displayed in the exhibition and retrace my process. The films screened on an immersive 4.20m wide installation and were accompanied by films I created from walking in the completed VR-landscape to offer another entry to the landscape than wearing the VR-goggles. Since being first exhibited for my masters degree in 2022, the entire work walkingwhiledrawing in Parnidis Dune has been displayed at several places at FH Bielefeld in Germany and can be set up in a range of configurations which can be seen on the pictures provided.

The VR-landscape Parnidnis Dune can be experienced with VR-goggles at any time and can be found in the Oculus animation store under the title Parnidis Dune / walkingwhiledrawing. Other images and more detailed text on the development of the project can be found on my website.

As walkingwhiledrawing is an ongoing project, I see Parnidis Dune as one piece of a larger process.

I have since found another landscape on Björkö Sweden, an island which I recreated in VR and that has also been displayed in conjunction with live music performed with musicians that were improvising to the screened films. In this project I also used filmed footage that I made on-site for the first time. I am interested in experimenting with further visual recording techniques and mixing different media as well as working with sound and written words to combine more layers forming a multimedia landscape collage.

The winners and honourable mentions of the Marŝarto Awards 2023 will be announced in February 2024.