With a direction out there – readwalking with thoreau, Emmanuelle Waeckerlé a French, London-based, artist, has created a cross-media interpretation of Henry David Thoreau’s text Walking.

a direction out there is one of the shortlisted pieces in the Sound Walk September Awards 2021.

Here, Emmanuelle dives into her reasoning behind the creation of her piece.

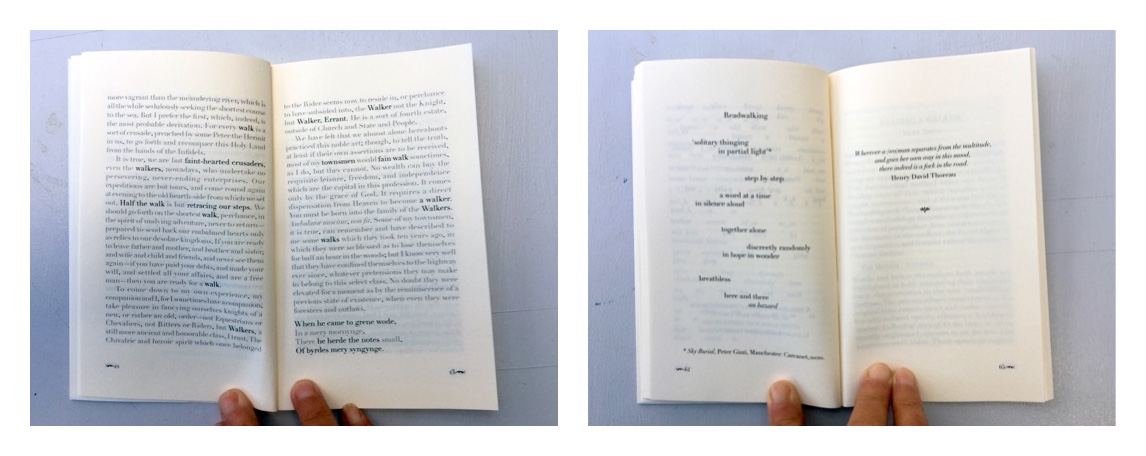

Henry David Thoreau’s transcendental lecture/essay, Walking (1851), after pruning, becomes conceptual poetry with an accompanying text score for reading, walking, speaking, singing, playing.

A reading path leads through Thoreau’s words kept as faint traces and visible root of my rewilding of the original text. This mise en abyme reveals endless potential paths. A preface and footnotes provide suggestions on how to speak or sound the remaining words, alone or with others, inside or outside.

Emmanuelle Waeckerlé’s score lifts the materiality of the text out of its ordinary fusion with the flows of meaning and rumination. Read-walking Thoreau, even in one’s own mind, has the salutary effect of an acupuncture of the spacetime of reading. Constellations of ideas virtually glow around Thoreau’s grey-scaled text.

Cécile Malaspina

To walk is to journey in the mind as much as in the land… And to read is to journey on the page as much as in the mind. Far from being rigidly partitioned, there is a constant traffic between these terrains, respectively mental and material, through the gateway of the senses.

Tim Ingold, 2011

The prepared text is an imaginary landscape, on which a few words stand out among commas, colons and full stops. We are asked to readwalk a handful of steps per page, to readwalk a sonic path through scattered words and punctuation marks, taking our time always. A path we each create word by word as we encounter them on the skin of the page with our mind’s eyes, and step by step on the ground with the skin of our feet.

We are living in chaotic times and according to Franco Berardi (Breathing: Chaos and Poetry, 2019), “Chaos is constituted of two different complimentary movements. The swirling flows of our surroundings and our attempt to reconcile this overwhelming flow with our own intimate internal rhythm of interpretation“. So that we are constantly seeking a tuning in to the surrounding chaos, attempting to keep up or catch up always, having to shut down, sometimes.

Readwalking allows for such a momentary tuning in of our breathing and walking and thinking by (re)connecting mind body and environment at a walking, reading or thinking pace that can sustain that connection.

Language is like a road, it cannot be perceived all at once because it unfolds in time, whether heard or read. This narrative of temporal elements has made writing and walking resemble each other in ways art and walking do not – until the 1960s.

Rebecca Solnit, 2014

I have explored quite extensively for the past 15 years, the parallel between walking reading and writing, as simultaneous acts of marking and reading (space), be it a page or a path. As well as the notion of a ballad, which in French is both a song and a walk. Doing so through Fluxus like poetic text scores and their activation in participatory performances, workshops, installation, concerts; SLOW MARCH (2001), roadworks (1996, 1998), JUNGLE FEVER (2011, current), PRAELUDERE (2013).

The project as a whole also develops further my interest in appropriation through experimental re-writing and reading of literary works that started with Reading (story of) O (Uniform books, 2015) and Ode (owed) to O (Edition Wandelweiser, 2017) then Black and Blue (2020) based on Rebecca Solnit’s book Hope in the Dark (2003/2016), Song of an Intention (2019) and Still Light (2020) based on Luce Irigaray’s To be two (2000).

A few years ago, I came across Thoreau’s transcendental and foundational essay about walking, as part of my preliminary research on contemporary walking practices for a book chapter I was writing about the JUNGLE FEVER (wish you were here) project. It was not relevant to what I was writing at the time but I knew I would go back to it at some point.

Walking, or sometimes referred to as “The Wild”, is a lecture by Henry David Thoreau first delivered at the Concord Lyceum on April 23, 1851. It was written between 1851 and 1860, but parts were extracted from his earlier journals. Thoreau read the piece a total of ten times. He considered it one of his seminal works, so much so, that he once wrote of the lecture, “I regard this as a sort of introduction to all that I may write hereafter. “Walking” was first published as an essay after his death in 1862. For Thoreau walking is a self-reflective spiritual act that occurs only when you are away from society, that allows you to learn about who you are, and find other aspects of yourself that have been chipped away by society.

Walking (Wikipedia)

What I did in 2018, after being occupied for a few years with a reading through of Pauline Reage Histoire d’O / Story of O, (1954 / 1965) finding a path, as a reader and as a woman through an infamous erotic novel that began as a series of private love letters written by the author to her lover. Reading (story of) O (uniformbooks 2015) reprints a graphic reworking of the original story, alongside its little know publishing history and a score for private or public collective readings. Ode (owed to) O (Wandelweiser, 2017) contains sonic renditions of the book and associated text scores ( O(nly), (story of), O(hhh).

Why?

Thoreau’s lecture /essay explores the parallel between walking and writing and reading in both content and form. The text promotes walking as an almost spiritual experience. JUNGLE FEVER (2011) proposes something similar.

Yet the text itself, written in 1851, is old fashioned in its long declamatory form of narration and turn of phrase, it feels very gendered: women are only referred to twice, in passing, being pitied for being denied the right to walk. It is also outdated in the way it addresses or not today’s pressing issues; climate change, pollution, decline of natural environment, rambling laws, etc..

How?

I am not the first to revisit Thoreau. I am in good company; Susan Howe greatly named poem Thorow (1990), phonetic misspelling of Thoreauand John Cage Mureau, (1970) a portemanteau word of music and Thoreau for a work based on his journals, in which Cage chose words and sentences referring to sounds and silence, as the source material for an elaborate and mostly nonsensical collaged piece of visual poetry meant to be spoken.

There is an old verb in French, abluer, which means in a bibliophilic context, to restore a printed text by cleaning the page of stains and reviving the ink. Something I have done to my previous reworking of existing litterature in Reading (story of) O (2015), conceptually cleaning the text of its toxicity / pornographic content and freeing the character O from her story.

My initial intention here was to refresh Thoreau’s lecture/essay and to undertake some kind of careful ablution. Not to erase or delete any of it, but to prune the text the way you prune a fruit tree, getting rid of what is old, while also making space for the fruits that are ripe at that particular time. Pruning an old but well-loved text like a gardener looks after an old bush, discarding what is no longer useful, or letting some light through to reach the inner branches. Pruning an old but well-loved text to make a path for oneself through a jungle of words and ideas. And to find ways to allow others to do so too.

So I kept the original text printed in light grey, highlighting in black a few scattered words per page chosen according to a simple set of rules. I started quite systematically by keeping all words relating to walking or how to do so. Then added a few here and there that provided a mental landscape for the readwalking eyes. Then a few more that I identified as Thoreau’s thinking while walking, I put these in bracket. And finally some sentences that I felt resonated or echoed with today’s chaotic world.

The transcendental lecture was spoken first, before becoming print. So I wanted to bring it back to speech and to sound somehow. I did so by proposing a text score with footnotes giving various suggestions on how to speak, un-speak, sing or sound the scattered words and punctuation marks, whether one is sitting or walking, alone or with others, inside or outside.

So that, Thoreau’s words can be read as a literary (original text) or poetic (pruned text) work, both intertwined on the pages of the pocket size book, or be transformed into a spoken or musical work which is conceived, not from notation, but from words used as both sound objects and meaningful signs, as in John Cage’s Mureau or Empty Words (1974), an epic text in four parts also drawn from the journals of Henry David Thoreau.

Four of these readwalking ballades (walks and their audio traces) are available on a double CD and on bandcamp alongside a few other ‘directions out there’ that I am uploading as I receive them and four recordings of performances of the prepared text that took place in Düsseldorf for Klangraum 2021 “day by day”.

Wherever a (wo)man separates from the multitude, and goes her own way in this mood, there indeed is a fork in the road’. Life without principle

Henry David Thoreau, 1863

Emmanuelle’s article is the fourth in a series of the artists shortlisted for the Sound Walk September 2021 Awards talking about their work.